Subscribe to our newsletter

Enter your email address below and subscribe to our newsletter

By Jules McJules

We’ve all seen ‘em, the beautiful but morose still-life paintings with the jewelry and the skulls. Vanitas paintings are a staple for any goth aesthetic, the fancier the better. But what are they? Where did they come from?

The vanitas style did not appear on a whim – religious unrest clashed with the newfound luxuries of capitalism in 17th century Europe. Artists have always loved expressing their thoughts on civil discourse, and some movements of the time were quite austere by comparison. Old, pious women had already begun to replace the famed artistic nudes from the Renaissance in an effort to desexualize art and culture, and still-life was also gaining popularity. Artistically, the idea of “memento mori,” or, “remember you will die,” dates as far back as the Middle Ages. Elderly, even biblical, subject matter paintings as well as the lush vanitas works were equally concerned with getting their audience to contemplate the inevitability of death. Colors also became much more muted, not just in paintings but in the way people dressed and decorated their homes as well. Through self-expression, people were grappling with morality and mortality taking on a new meaning.

The method by which the artist gets their audience to contemplate life is the focus in this style. There were other types of still-life paintings that did not stir these questions: think of any innocuous bowl of fruit, or a bouquet, something that sits still on a table. Economically, importing trade goods naturally led to class luxury. The new practice of commodifying everything had vanitas artists asking what items we collect, and why. The ‘real’ value or spiritual validity of such transient goods of pleasure was being questioned. Visual works juxtaposing abundant food and glittering jewels next to literal death and decay was cathartic – it stirred the questions too abstract to ask. Death is not a finality, but a necessary part of life, in some ways giving it meaning.

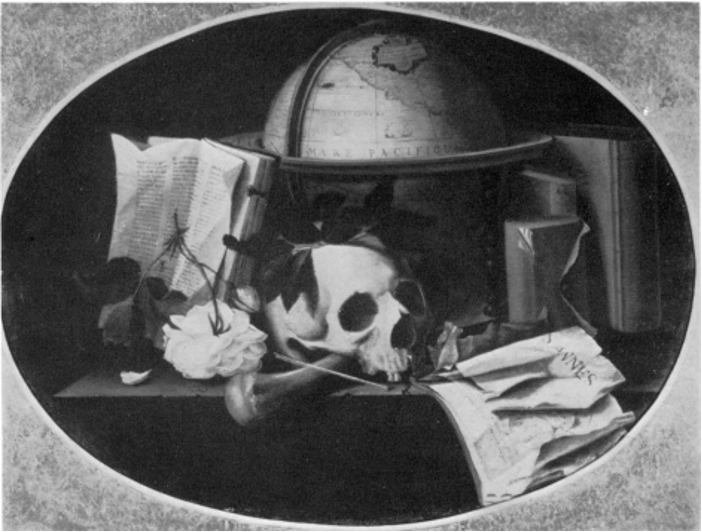

There can be no denying the beauty that is found in these paintings. Some examples:

A skull – a literal representation of death – is center frame, no ambiguity, but crowned in laurel leaves to show respect. Two roses are featured to the left, one at the start of its life cycle and one at the end. The globe towers over everything, implying that these concepts of death and transition are universal. The artist also ‘collects’ intellectualism with books. Encircling all of this is many books, some open, some closed, many pages showing damage from continual use, as is their purpose. At first one might see a cluttered desk, but beauty pulls the viewer in, and the composition has one’s eye and the mind churning while taking it in.

Decadence is on the outside frame while death is, once again, in the center. The rose at the bottom left is halfway between these, having been cut a while ago yet only just past its prime, as flowers have a longer afterlife than animals do. Instead of a skull, a bouquet of dead birds, not yet in any sort of decay. One can only tell they are dead, not sleeping, by the particular limpness of their necks and the way they are piled atop each other. In this manner they are able to thrust upon the observer the reminder of death in a way that cooked birds at dinner time never could. However, these birds are beautiful. The colours, the feathers and their texture, the patience and skill that went into depicting them as lifelike as possible is all very graceful and overall pleasing to look at. Art historian Paul Barlosky said it best: “Pictures like van den Berghe’s were painted to be hung on walls to be, dare I say, enjoyed; and, yes, if they prompted the beholder to contemplate mortality, they also most emphatically beautified, enhanced, the lives of those who lived in spaces adorned by such pleasing illusions, by such pleasurable demonstrations of artistic skill in the representation of life’s pleasures.”

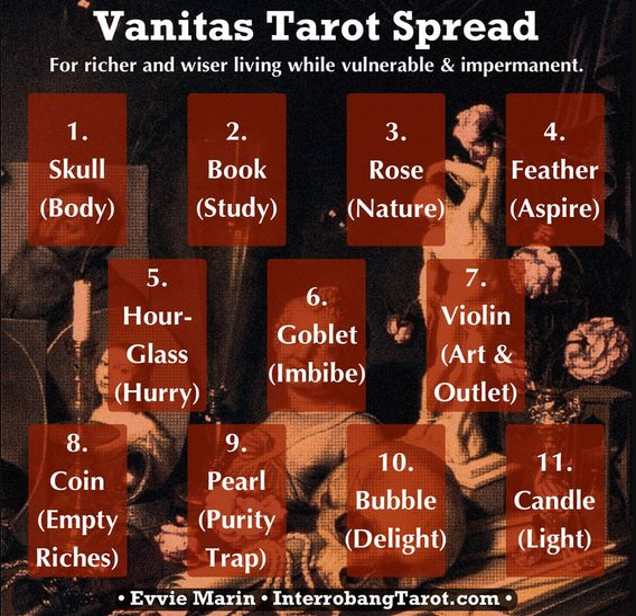

One final example for contemplation – a tarot spread, an art both visual and performative, of the contemporary Neo-Pagan/New Age practice, that I discovered some years ago just casually scrolling through Pinterest. There is not much analysis I can do here that is not already explained in the clipping itself. Each space is where the reader is to place a card, the traditional vanitas symbols are labeled with easy interpretation correlating to their symbolism, and this type of spread is meant for the querent to reflect on their life, where it is and what it means and where they want it to go. Although tarot is often associated with future-telling, this art of divination is just as frequently if not more-so concerned with present-telling and an invitation to self-awareness in both action and values. In my opinion, the card slinger who came up with using classic Dutch vanitas style for this pre-existing purpose had no less than a stroke of genius.

Vanitas paintings deliberately used beauty to grapple with moral values and the division between idealism and everyday life. Other Dutch paintings were also portrayed ‘as they are’ – that is, portraits of people doing things that were common to Dutch life, as opposed to having models posed in an idealized fashion. In this way were the vanitas paintings – it’s not about a pictorial representation of what was there, it was about an easily understood examination of what the average person was experiencing. Classical art needed to be studied to understand the symbology, but bones next to a bouquet of fully bloomed flowers lit by worn-out candles could jar the pedestrian into contemplating loss, beauty, and temporary states of being.

How lucky are we that these artistic reflections are not as transient as their subject matter reminds us all things must be.